1 How the Digestive System Works

2 Poo Eating (Coprophagy)

3 Health Monitoring: Weighing vs. Poos Watching

- What does weighing do?

- What does the poop output tell you?

4 Minor Poop Issues

- How to deal with a minor tummy upset

- Funny poops: What do they mean?

- Caked on poops

5 Serious Diarrhoea

6 Impaction

7 Worming: Yes or no?

Wiebke's Guides are a series of articles I have written for Guinea Pig Magazine in 2023 and 2024.

They are there to help you understand how the urinary tract works, learn to spot what is normal and what not and what are the most common health issues connected with it.

1 How the Digestive System Works

Guinea pigs are truly mainly a gut with a big food wheek attached. The digestive system takes up the most space inside the body with a comparatively very small respiratory system tucked into the rather small chest together with the heart.

The caecum part of the gut where the fermentation happens makes by far the largest part of the gastro-intestinal tract: it takes up about two thirds of the whole gut, so it is the part where the food stays longest and where you will find most of the eaten food at any given time. Because the digestive system in guinea pigs is not as effective, the gut is overall comparatively larger and heavier than that of rabbits and makes them less agile.

New research has shown that it takes about 8-30 hours from mouth to anus – it takes about 2 hours for any intake to pass the stomach into the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum) where it is broken down into smaller particles. But it takes around 20 hours in the large fermentation part of the gut, the caecum, for any nutrition to be passed on towards the exit via the colon and the anus, where it is formed into poos; the latter form together the large intestine.

Most bloating happens in the caecum when the fermentation process derails (the classic bloat) but bloating can affect other parts of the gut, even the stomach as I know from a personal experience.

Some vets now think that the rather ineffective way oral medication is absorbed (meaning that they need comparatively much higher dosages than other animals of comparative weight) could lie in the way food is processed in the caecum. More research will be needed but we will hopefully get some answers in the not too far future.

The gut microbiome is retained by a mucus trap in a groove in the colon. This accounts for the occasional bits of mucus in and around poos or as baffling mucus blobs on the bedding – they are parts of the barrier that have slipped through. A one-off appearance is not to worry (unless your piggy is clearly unwell) but if you see mucus several times within a matter of days, a trip to the vet may be advised; the latter case is however rare.

On the whole, it takes about a whole day (ca. 24 hours) for any food from one end to the other. Food passes fastest with runny diarrhoea (when the fermentation and especially the firming up doesn’t happen) and is usually slowest after GI stasis, heat stroke or severe illness without much food intake for several days.

2 Poo Eating (Coprophagy)

Like a number of other species, guinea pigs eat some of their poos; usually directly from the bum as fresh as possible for a second run through the gut in order to break down further the highly nutritious but tough grass/hay fibre, which makes over three quarters of their daily food intake.

New research has shown that unlike rabbits guinea pigs are coprophages. This means literally ‘poo eaters’. Guinea pigs just eat some of their normal poos for a normal second run through the gut to better their overall fibre, vitamin and trace elements uptake. These re-digested second run poos are officially called coprotrophs in order to distinguish them from those that rabbits and their fellow lagomorphs make. Their special bundles of small fibres that are formed in the caecum are called caecotrophs but are more advanced and effective compared to what guinea pigs produce.

The second run through the gut improves the nutrient absorption from the hay/grass fibre and is crucial for long term health. That is why you see many older piggies that are no longer mobile enough to pick up the poos straight from the anus turn quickly around to pick them up from the floor; they can become rather upset when they cannot find them. The longer a poop is outside the body, the less use it becomes. This happens very quickly and is also the reason why poo soup can only be made from just dropped healthy poos, not ones lying around the cage.

Guinea pigs that are not able to eat their poos, like more majorly impacted boars, guinea pigs with back leg paralysis, very ill guinea pigs or piggies unable to pick up food can experience a decrease in weight, a diminished fibre uptake and a loos of minerals, especially over longer periods.

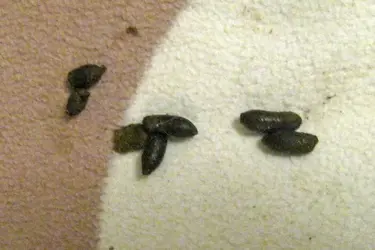

Coprotrophs (poos from the second run) are usually a touch harder than the no longer needed freshly excreted poos from the first run.

However, this means that some poos that come out at the other end have taken a full two days to get there, not just one day – and that is in a normally working gut. When poo monitoring, this is important to know.

2 Poo Eating (Coprophagy)

3 Health Monitoring: Weighing vs. Poos Watching

- What does weighing do?

- What does the poop output tell you?

4 Minor Poop Issues

- How to deal with a minor tummy upset

- Funny poops: What do they mean?

- Caked on poops

5 Serious Diarrhoea

6 Impaction

7 Worming: Yes or no?

Wiebke's Guides are a series of articles I have written for Guinea Pig Magazine in 2023 and 2024.

They are there to help you understand how the urinary tract works, learn to spot what is normal and what not and what are the most common health issues connected with it.

1 How the Digestive System Works

Guinea pigs are truly mainly a gut with a big food wheek attached. The digestive system takes up the most space inside the body with a comparatively very small respiratory system tucked into the rather small chest together with the heart.

The caecum part of the gut where the fermentation happens makes by far the largest part of the gastro-intestinal tract: it takes up about two thirds of the whole gut, so it is the part where the food stays longest and where you will find most of the eaten food at any given time. Because the digestive system in guinea pigs is not as effective, the gut is overall comparatively larger and heavier than that of rabbits and makes them less agile.

New research has shown that it takes about 8-30 hours from mouth to anus – it takes about 2 hours for any intake to pass the stomach into the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum) where it is broken down into smaller particles. But it takes around 20 hours in the large fermentation part of the gut, the caecum, for any nutrition to be passed on towards the exit via the colon and the anus, where it is formed into poos; the latter form together the large intestine.

Most bloating happens in the caecum when the fermentation process derails (the classic bloat) but bloating can affect other parts of the gut, even the stomach as I know from a personal experience.

Some vets now think that the rather ineffective way oral medication is absorbed (meaning that they need comparatively much higher dosages than other animals of comparative weight) could lie in the way food is processed in the caecum. More research will be needed but we will hopefully get some answers in the not too far future.

The gut microbiome is retained by a mucus trap in a groove in the colon. This accounts for the occasional bits of mucus in and around poos or as baffling mucus blobs on the bedding – they are parts of the barrier that have slipped through. A one-off appearance is not to worry (unless your piggy is clearly unwell) but if you see mucus several times within a matter of days, a trip to the vet may be advised; the latter case is however rare.

On the whole, it takes about a whole day (ca. 24 hours) for any food from one end to the other. Food passes fastest with runny diarrhoea (when the fermentation and especially the firming up doesn’t happen) and is usually slowest after GI stasis, heat stroke or severe illness without much food intake for several days.

2 Poo Eating (Coprophagy)

Like a number of other species, guinea pigs eat some of their poos; usually directly from the bum as fresh as possible for a second run through the gut in order to break down further the highly nutritious but tough grass/hay fibre, which makes over three quarters of their daily food intake.

New research has shown that unlike rabbits guinea pigs are coprophages. This means literally ‘poo eaters’. Guinea pigs just eat some of their normal poos for a normal second run through the gut to better their overall fibre, vitamin and trace elements uptake. These re-digested second run poos are officially called coprotrophs in order to distinguish them from those that rabbits and their fellow lagomorphs make. Their special bundles of small fibres that are formed in the caecum are called caecotrophs but are more advanced and effective compared to what guinea pigs produce.

The second run through the gut improves the nutrient absorption from the hay/grass fibre and is crucial for long term health. That is why you see many older piggies that are no longer mobile enough to pick up the poos straight from the anus turn quickly around to pick them up from the floor; they can become rather upset when they cannot find them. The longer a poop is outside the body, the less use it becomes. This happens very quickly and is also the reason why poo soup can only be made from just dropped healthy poos, not ones lying around the cage.

Guinea pigs that are not able to eat their poos, like more majorly impacted boars, guinea pigs with back leg paralysis, very ill guinea pigs or piggies unable to pick up food can experience a decrease in weight, a diminished fibre uptake and a loos of minerals, especially over longer periods.

Coprotrophs (poos from the second run) are usually a touch harder than the no longer needed freshly excreted poos from the first run.

However, this means that some poos that come out at the other end have taken a full two days to get there, not just one day – and that is in a normally working gut. When poo monitoring, this is important to know.